The Rediscovery of Roman Epigraphy in Europe

After the Middle Ages, when classical art, literature and philosophy was largely ignored or forgotten, the Renaissance saw a passionate ‘rebirth’ of interest in classical antiquity. Artists such as Da Vinci, Michaelangelo and Raphael drew influence from the Roman sculptures, coins and gems being excavated in Rome during the 15th and 16th century. When ancient sculptures such as the Laocoon were discovered, they became celebrated and influential, finding prominent places in the sculpture collections of the Vatican as well as the nobility of Rome, adorning many private houses, often in the gardens.

Etching with engraving

Jan and Lucas van Doetecum, etchers

Hieronymus Cock, publisher

[1551-1561?]

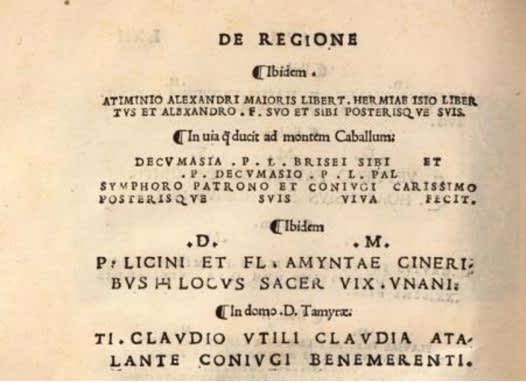

The Renaissance also saw a rediscovery of Latin and Greek inscriptions. Such texts remained legible on many ancient monuments and fragments in the city of Rome and there became a great interest in studying those texts and trying to link them to ‘modern’ life. There is something extremely compelling about reading the words of those who have gone before you, from great public political statements of emperors, to small epitaphs of the freedmen and women who lived, worked and died in ancient Rome, their names preserved for posterity. The cinerary urn of Tiberius Claudius Utilis set up by his wife Claudia Atalante is just such an example. Simply from their names we can conclude that he may well have been a freedman (or a descendant of such) manumitted in the Claudian family before it became imperial: possibly freed by Tiberius before he was adopted into the Julian family in AD 4 (after which date his freedmen would be named Ti(berius) Iulius); and since she is 'Claudia', she may have been his freedwoman originally, possibly of Greek origin from her mythological name.

DEDICATED BY CLAUDIA ATALANTE FOR

HER HUSBAND TIBERIUS CLAUDIUS UTILIS

Tiberian to Claudian, circa 1st half of the 1st century AD

With Kallos Gallery

GIULIO POMPONIO LETO & HIS CIRCLE

It was during the Renaissance that numerous antiquarians began recording Latin inscriptions, especially in Rome. The humanist Giulio Pomponio Leto and his fellow Royal Academicians explored the catacombs of Rome and in 1494 Pietro Sabino, a part of Pomponio Leto's group of academics, compiled a list of Christian inscriptions found there. This partly survives in a codex in the Vatican Library (Cod. Ottob., Vat. 2015) and the urn of Tiberius Claudius Utilis (pictured above) is listed there as being in the collection of Cardinal Colonna. The next recorded owner 'Tamyra' is provided by Jacobus Mazochius in 1521. This probably refers to Piero Tamira (1465 - after 1519), who was a Latin poet, also connected with Pomponio Leto's circle in Rome.

Mazochius, 1521

It wasn’t just humanist scholars who were interested in such inscriptions. The cinerary urn for Pamphile (pictured below) is recorded as having been in the collections of artists and sculptors of the Baroque period in Rome: the artist Girolamo Odam (1681 – 1741), and then with the sculptor Carlo Antonio Napolioni (1675 – 1742), who was the official restorer to the Museo Capitolino and who famously restored the rosso antico Capitoline Faun excavated at Hadrian’s villa at Tivoli in 1736.

A ROMAN MARBLE CINERARY URN INSCRIBED FOR PAMPHILE

Circa 1st century AD

Height: 21.6 cm; length: 38.7 cm; depth: 26.7 cm

With Kallos Gallery

THE GRAND TOUR AND GREAT BRITISH COLLECTORS

The passion for studying and collecting ancient art grew exponentially with the rise of the Grand Tour where wealthy young men would visit the Continent to ‘finish’ their education as a gentleman. This always included Italy but could also take in the sights of Greece and Turkey. It became highly fashionable to establish a reputation as a collector and connoisseur and become a Member of the Society of Dilettanti. By the end of the 18th century, the Society was the premier British society for the study of classical antiquities.

One just such dilettante was William Ponsonby, Viscount Duncannon and later 2nd Earl of Bessborough (1704-1793). The urn for Tiberius Claudius Utilis is probably one of several that he acquired in Italy, alongside a large collection of other fine marbles and gems (many of which formed the Marlborough Collection). Bessborough commissioned Parkstead (pictured below), a grand classical villa at Roehampton to house his collection and the cinerary urns were displayed in what Bessborough called his catacombs. This seems to have been a vaulted area fitted with niches to imitate an ancient columbarium.

As an anonymous poet wrote:

“Here Genius, Taste, and Science stand confest

And fill the minds of each transposed Guest...

Where e’r we turn; where’er we look around

We seem to breathe and tread on Classic Ground…

Ask ye, from whence these various Treasures come

These scenes of wonder? Need I Bessborough name?”

Following the death of Bessborough, his collection was sold at Christie’s in 1801. The Tiberius Claudius Utilis urn was subsequently acquired by William, Second Earl of Lonsdale who formed a magnificent collection of inscriptions at the family seat Lowther Castle in Penrith (pictured below). Many of the Lowther Castle inscriptions are recorded by Michaelis as having come from the Bessborough Collection and were displayed at Lowther in the ‘lapidarium’, a passage leading from the East Gallery to the Billiards Room, containing ‘one hundred and twenty-three Roman sepulchral inscriptions’ (A. Michaelis, Ancient Marbles in Great Britain, Cambridge, 1882).

Like many other private collections, the Lowther collection of inscriptions was sold shortly after the second world war. Damage sustained by the castle, combined with increasing family debts, meant that in 1947, the collection, including the urn for Tiberus Claudius Utilis was put up for auction through Sotheby’s and sold.