'Women therefore inspire love even when made of stone', Pseudo-Lucian, Amores 17

Praxiteles’ Knidian Aphrodite was produced in the mid-4th century BC, and is supposedly the first monumental cult statue of a goddess to be represented nude. Praxiteles’ revolutionary creation has had a huge influence on western art, and her popularity is expressed in the numerous adaptations and copies in antiquity down to the present day. Her famous pose with her hand covering her modesty has been one of the most represented artistic configurations in the western world, and was given the name pudica meaning ‘modest pose’.

According to Pliny the Elder (Natural History, 36. 20-1) Praxiteles made two marble statues of Aphrodite and sold them at the same time. One was clothed, which the sculptor sold to the polis of Kos. This draped version appealed more to the Koans because they judged it “serious and modest”. The nude statue of Aphrodite was sold to the polis of Knidos (a Greek city in Asia Minor), where she became an immensely popular tourist destination, and according to Pliny, was superior above all other creations. The pudica pose is extremely ambiguous and has resulted in long standing debates amongst scholars as to how the statue should be read and viewed.

THE LUDOVISI KNIDIAN APHRODITE (CCBY-SA-4.0)

The Roman National Museum, Palazzo Altemps, Rome, inv.no. 8619

In this week’s insight we will explore two of the main debates examining how the Knidian Aphrodite may have been viewed in antiquity. Was she purely viewed as the subject of the male gaze, idealised as an erotic image for male pleasure? Or did the sculpture beckon the viewer in under the goddess’s own terms making her the active subject?

The theory of the ‘male-gaze’ as the key structuring principle for the representation of women, was born during the growth in feminist debate stemming from Second Wave feminism, and the theory has challenged our concept of looking ever since. Within the discipline of ancient art history the starting point for this is an examination of the female nude as the masculine ideal of aesthetic beauty, specifically Praxiteles’ Knidian Aphrodite.

After the creation of the Knidian Aphrodite, the goddess Aphrodite was predominately depicted nude, and even when she was shown clothed there were still subtle allusions to her sexuality. For example with the Kallos Roman marble statue of Venus Genetrix, the use of wet drapery has been used suggestively to display the contours of her form beneath. With the Knidian Aphrodite, her nudity is sexually coded by the ambiguous placement of her right hand covering her pubis. This gesture, the turn of her head, and the way the goddess looks to be trying to cover herself, creates the impression that the viewer has intruded into her private act of bathing. Her body language constructs a narrative that the viewer has been drawn to something we are not permitted to see.

ROMAN MARBLE STATUE OF VENUS GENETRIX

Circa 1st century BC

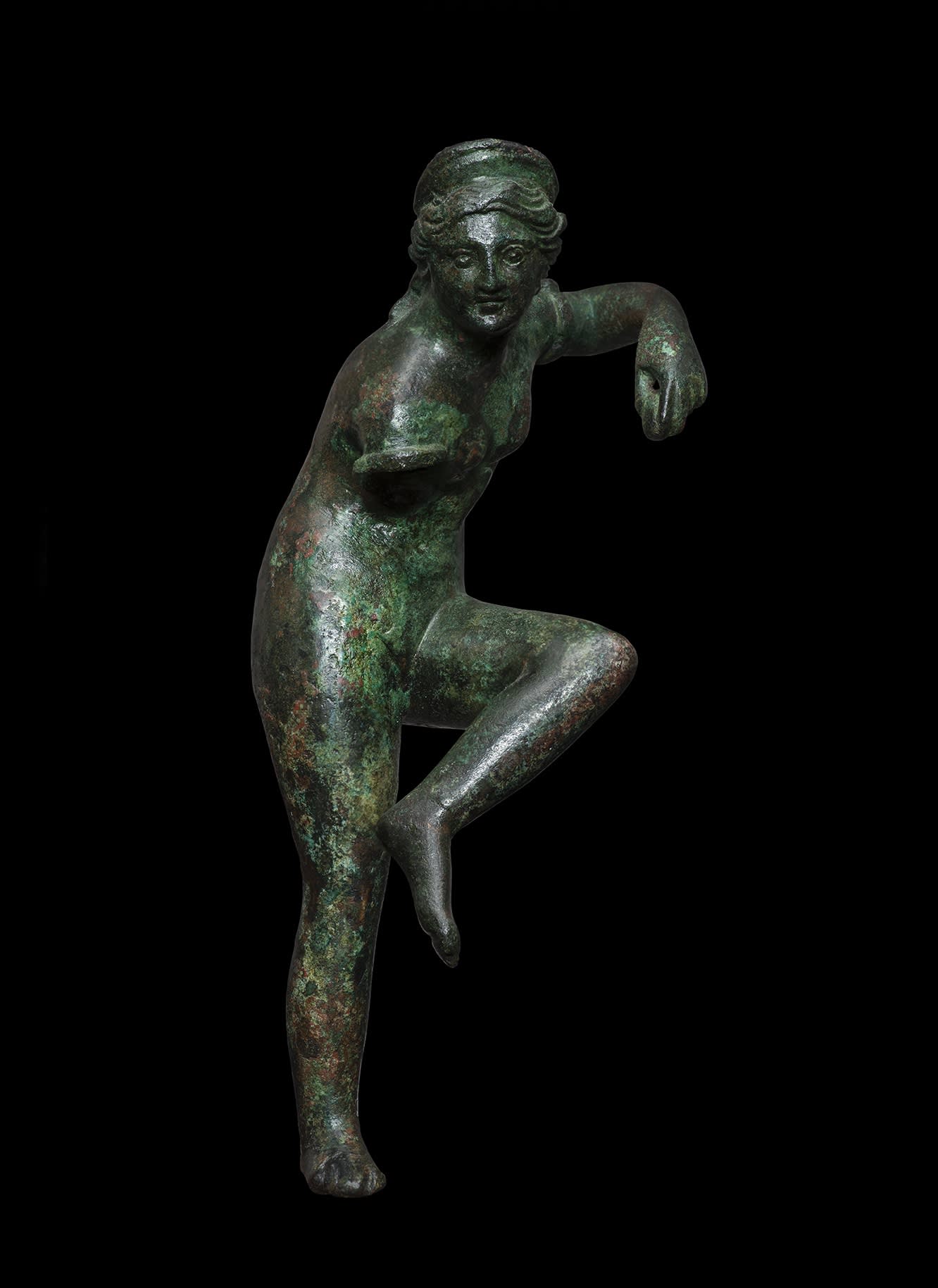

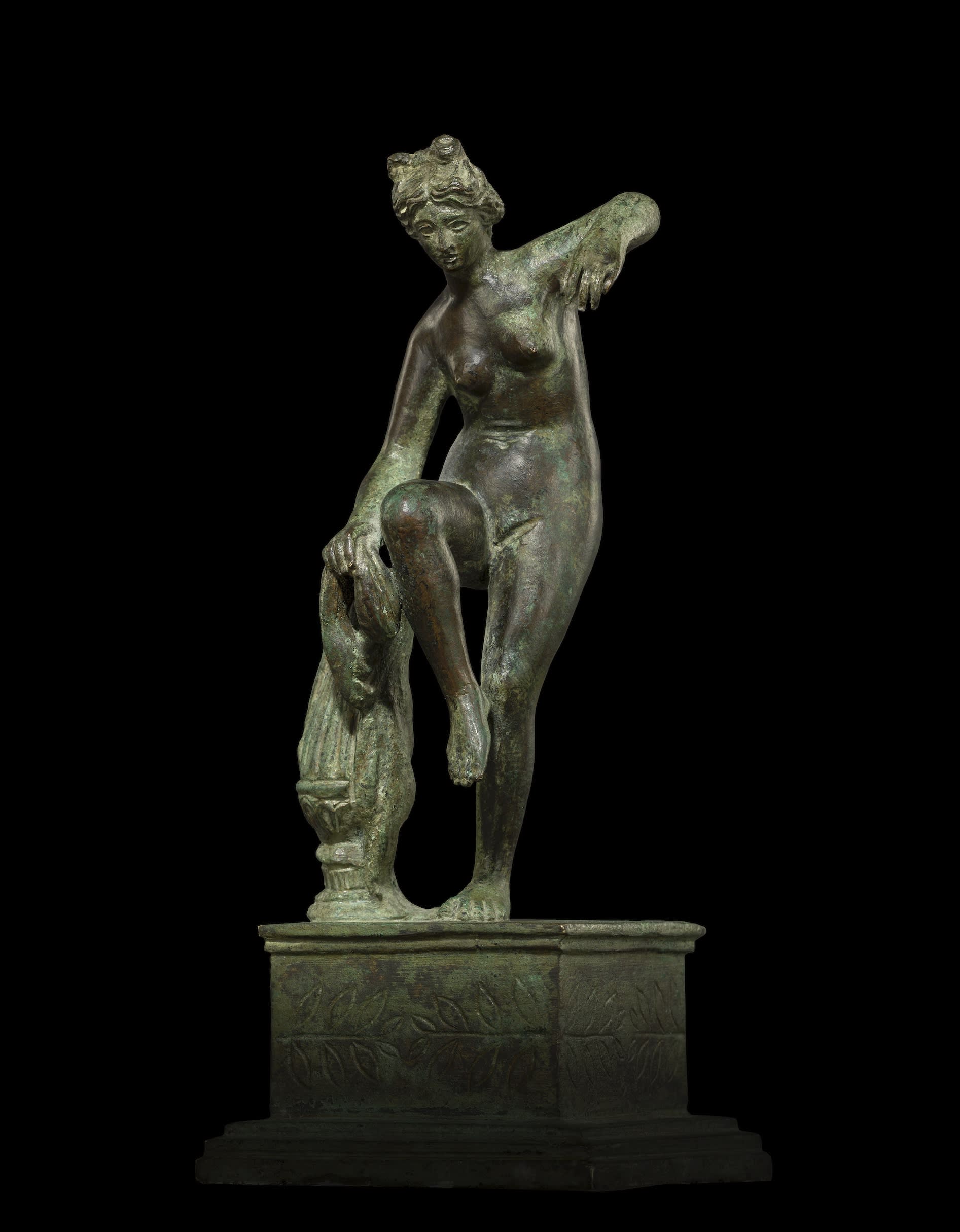

The fetishistic quality of the pose is also captured by the testimony of the reactions of ancient viewers to the Knidian Aphrodite. Two key accounts describing the sculpture come from Pliny the Elder (Natural History, 36. 20-1) and the pseudo-Lucian (Amores, 13–14), which provide an important insight into how the Knidian Aphrodite was viewed and received in the ancient world. Pliny states that the sculpture’s shrine was “completely open, so that it is possible to observe the image of the goddess from every side”. This is also true of the successors of the Knidian Aphrodite, such as depictions of the nude goddess untying or adjusting her sandal. This motif was developed during the Hellenistic period and became popular in the Roman period, especially in smaller bronze interpretations. For example with the Kallos Roman bronze figure of Venus the goddess can be seen from all angles, and again we have caught her in a moment and in a pose that highlights her sensuality.

A ROMAN BRONZE FIGURE OF VENUS UNTYING HER SANDAL

Circa 1st-2nd century AD

A ROMAN BRONZE FIGURE OF VENUS

Circa 1st century AD

Archaeological evidence suggests that the setting for the Knidian Aphrodite was a fine Doric rotunda placed high up on a terrace at Knidos overlooking the junction between the Aegean and the Mediterranean proper. This circular columned setting would have allowed the observer to gaze at the goddess through the columns as they moved around the shrine. This setting transforms the viewer into a voyeur as he/her becomes a ‘peeping tom’ stealing desirable glances unbeknown to the goddess. In addition, the Amores attributed to the pseudo-Lucian, provides a fictional account of the psychological experience of three friends’ visit to the Knidian Aphrodite’s shrine. In the description of the sculpture, Aphrodite’s body parts are divided up and reduced into idealised fragments as they recount her “rounded thighs, begging to be caressed”, and the “tenderness of her smile”.

Perhaps the most famous account mentioned by both Pliny and the pseudo – Lucian is the tale of the young man so infatuated by the statue that he contrived to have himself locked in the shrine with the goddess, where overcome with desire he left a stain on her thigh. From these accounts, combined with the above interpretation of the goddess’s pose, it is convincing that during antiquity the goddess was subjected and lowered to become an object of the male gaze.

However, in order to fully understand how the different depictions of Aphrodite may have been viewed in antiquity we have to analyse ancient Greek theories on the gaze and ancient theories on vision. For example Democritus proposed that every object emitted a simulacrum of itself, which travelled through the air to the eye and from there entered the psuche (soul). Therefore while looking at the Knidian Aphrodite the viewer believed that a tiny replica of her would physically enter his soul connecting with him/her. Pliny the Elder theorised that a ray would spring from the viewer’s eye, which would touch the statue and bring back an impression to the soul. These ancient theories see vision as something that touches the psuche directly, and therefore to gaze was also to react emotionally and physically and not necessarily in a domineering or sexual way.

These theories can also help us formulate a different interpretation of the pudica pose. Scholars such as Andrew Stewart have hypothesised that the sculpture has two sides; her ‘closed’ right side with her rigid contours, convex curves, and right hand covering her pubis repel the viewer’s eye. In contrast her left side with her softer contours, concave curves, and her welcoming gaze beckons the viewer in and encourages the viewer to move around her (A. Stewart, Art, Desire, and the Body, Cambridge, 1997, p. 103). The casualness of the supposedly protective gesture of her right hand is indicated by the fair distance of her hand from the part that the goddess wishes to protect. Her drapery is also not raised up near her breasts, which would be a natural reaction if she had just caught sight of a viewer watching her. The ‘S’ curve of her body and slight stoop in her back also seems to suggest that she has acknowledged an observer’s desiring glance and is beckoning them in, rather than it being a reflection of the goddess’s shame. In addition, in Lucian’s account he describes Aphrodite’s smile as huperephanon meaning arrogant, haughty, or proud. This suggests that through her ambiguous pose, the goddess does not conform to traditional female subservience by being the subject of the male gaze, but that in actively responding to the viewer, she has transformed them into the passive object.

Feminist theories on the male gaze can be used to open debates on modes of viewing depictions of Aphrodite in order to make us see things in a different way. However considering Aphrodite’s status as an all-powerful Greek goddess, who could reign down terror at any moment, it seems unlikely that her cult statue should be viewed as ashamed and sexually vulnerable. The fact that Aphrodite was the apotheosis of female sexuality, and that the essence of her sexuality was her body it makes sense that her body should be revealed. Applying this, combined with ancient theories on the gaze, it seems more likely that she should be viewed as capable of overwhelming the eroticised glance, while simultaneously maintaining her dignity and distance as a goddess. Although the Knidian Aphrodite illicits male desire and erotic possibilities, it is on her terms and not the viewers.