SLEEPING FIGURES IN ANCIENT ART

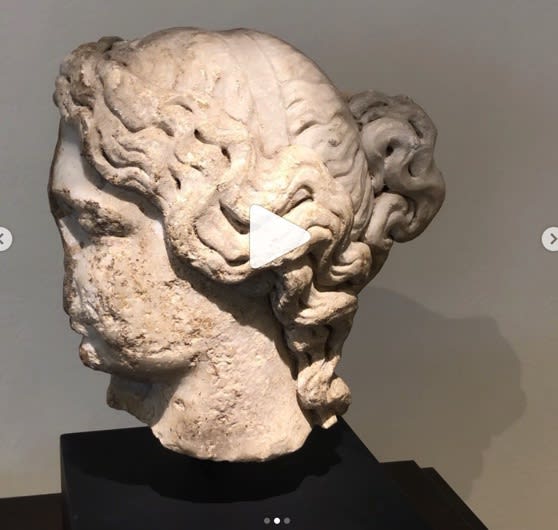

This marble head with its incredibly intricate hair arrangement is unusual, as it depicts a woman with her eyes shut, sleeping. Images of figures asleep occur in Graeco-Roman art in various media including vase painting, wall painting and sculpture. The sleeping figures depicted go in and out of fashion over the centuries, however the most commonly found mythological characters who are shown asleep, are Ariadne, the Hermaphrodite, Eros and Endymion.

There are very few sleeping figures depicted in the art of Archaic and Classical Greece, but the subject became more frequent in the Hellenistic period as the trend for realism and naturalism grew. It was during the Roman period however that images of figures asleep increased and diversified in subject. They were initially a popular element in wall painting and then in sculpture, especially on marble sarcophagi.

The two sleeping mythological figures with arguably the longest lasting popularity in Greek and Roman art were the maenad and Ariadne. Beazley believed that the earliest depiction of a sleeping maenad in vase-painting was by the Amasis Painter, from a now lost fragment of an amphora (Beazley archive no. 310445). The scene shows two satyrs embracing maenads, with a wine jug lying beside them. The jug is decorated with what appears to be a satyr clutching a reclining maenad, and it was this figure that Beazley regarded as the earliest representation.

The theme of satyrs approaching sleeping maenads became especially popular in Attic vase-painting. The satyrs are generally shown creeping towards a maenad who is usually reclining on a rock, with her head downturned and her limbs relaxed clearly showing she is asleep. Several vase-painters such as Makron also show pesky satyrs lifting her garment and peeking (Attic red-figure kylix, Museum of Fine Arts Boston, inv.no. 01.8072). In this particular example, the maenad can be seen clutching a thyrsus, which provides an alcohol-induced explanation for her sleep; she has gone out to enjoy some Dionysiac revelling and has taken refuge on a rock exhausted.

AN APULIAN RED-FIGURE BELL KRATER

Circa 380-360 BC

Depicts a satyr sneaking upon a sleeping maenad

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, inv.no. 1984.323.2

Ancient literary sources generally wrote very approvingly of sleep: it could help relieve, restore and enlighten. In Homer sleep is also regarded positively, and is often described using epithets such as ‘sweet, pleasant’, as it brought rest to the weary and could help relieve one’s sorrows. In visual art however, artists seem to treat sleep much more warily; it is shown as leaving characters vulnerable, weak and open to attack. The scenes of sleeping maenads shown above demonstrate the thought that physical danger is risked in the vulnerability of sleep.

BORGHESE SLEEPING HERMAPHRODITUS

Circa 2nd century AD

The Louvre, Paris, inv.no MR 220

CC BY-SA 3.0

In sculpture, the most renowned example is the Borghese Sleeping Hermaphroditus, now in the Louvre. A very closely related sculpture to this type is the Roman marble sleeping maenad currently in the National Archaeological Museum of Athens. Discovered in Athens, just south of the Acropolis the maenad is depicted resting on a rocky surface and lying on a panther skin. Dating to the 2nd century AD, this piece is similar in date and style to the Kallos example. Both share similarities in the intricacies of their hairstyles and both would most likely have been part of larger sculptural groups.

A ROMAN MARBLE SLEEPING MAENAD OR HERMAPHRODITE

Hadrianic, circa 2nd century AD

The National Archaeological Museum of Athens, inv. no.261

Sleeping maenads have often been identified as Ariadne, whose most early depictions slumbering are in Attic vase-painting, about a decade after the Amasis maenad. These scenes most commonly show Ariadne at the moment of her rescue by the god Dionysus. In Greek mythology, Ariadne was the daughter of King Minos of Crete. She helped the Athenian prince Theseus to kill the Minotaur living in the depths of the Labyrinth, by providing him with a ball of thread so he could find his way out of the maze. After Theseus’ victory he sails away taking Ariadne with him, however on the way to Athens he abandons her on the Island of Naxos. It is here that Dionysus discovers Ariadne and awakens her from her despair to make her his immortal bride.

The theme of sleeping Ariadne is commonly found on Roman wall paintings, and was a particularly dominant element in Campanian and Pompeiian painting. One fresco from Pompeii, and now in the National Archaeological Museum of Naples, for example shows the moment Dionysus discovers the sleeping Ariadne.

A ROMAN FRESCO FROM POMPEII

Circa 1st century AD

National Archaeological Museum of Naples, inv.no.9271

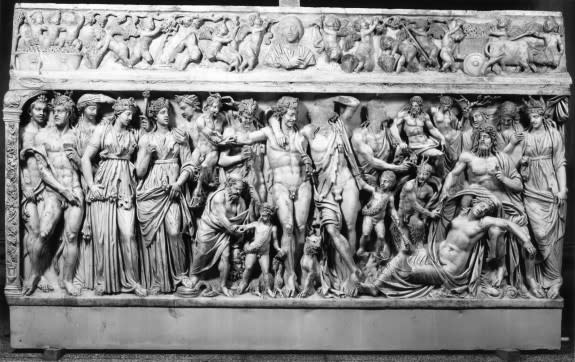

The sleeping theme was a particularly popular and of course, fitting motif on Roman marble sarcophagi. Full-length sleeping figures in the round were used to decorate lids as well as the main figural frieze on the front and around the body of the sarcophagus. Ariadne was a frequent subject, as was Endymion.

A ROMAN MARBLE SARCOPHAGUS WITH

DIONYSUS AND SLEEPING ARIADNE

Circa 190-200 AD

The Walters Art Museum, inv.no.23.37

There is one very notable sculpture in the round of sleeping Ariadne, which was acquired by Pope Julius II (1503-1513) and is housed in the Vatican Museum. The sculpture is a Roman copy of a 2nd century BC original from the school of Pergamon. The composition of the figure of Ariadne is very similar to the depictions on Attic vases, and shares the same theme of the troubled sleep Ariadne endures while abandoned on the island of Naxos.

A ROMAN MARBLE SCULPTURE OF SLEEPING ARIADNE

Hadrianic, circa 2nd century AD

The Vatican Museums, Rome, Cat. 548

CC BY-SA 3.0

Click here to head to our instagram to view a short video of the piece.