Egyptian

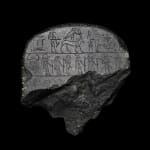

An Egyptian steatite magic cippus, Ptolemaic, circa 3rd century BC

Steatite

Dimensions: 16.5 cm x 15 cm

Further images

Preserving the upper part of the stele, the child Horus is depicted in typical nudity with his sidelock of youth, holding in his right hand a cobra and a scorpion,...

Preserving the upper part of the stele, the child Horus is depicted in typical nudity with his sidelock of youth, holding in his right hand a cobra and a scorpion, with three cobras in his left, he originally stood on crocodiles which are now missing. A head of Bes wearing a crown of feathers appears above. Inscribed on all sides with hieroglyphic text, magical signs, and protective deities. The divine figures are, top row, left to right: Thoth, then Horus on a gazelle (which is connected with the 16th Nome of Upper Egypt, and shows Horus of Hebenu the Nome's capital, now Kom el-Ahmar), then Min. The second row after the scarab: Sekhmet, an unidentified mummiform god, Seth, an unidentified goddess, a human headed god carrying crossed serpents (possibly Heka), and finally probably Herishef.

Provenance

Hans Blaser Collection, Kloten, Zurich, acquired in the 1970s

With Galerie Nefer, Zurich, 1991

Private collection, Switzerland, acquired from the above

Exhibitions

On Loan: Antikenmuseum Basel & Sammlung Ludwig, 1998 - 2022Literature

In Egyptian mythology, the goddess Isis raised Horus by hiding him in the marshes from his enemy, Seth. Such magical stelae, represent Horus’s healing from scorpion stings and snakebites in the marshes. To symbolise his magic powers, Horus holds snakes and scorpions in his closed fists. His feet originally rested on two crocodiles. The cippus essentially acts as an amulet inscribed with magical spells to ward off stings and bites from deadly animals and insects. The head of the protective god Bes above Horus, and the protective deities on the reverse, strengthens the magical power of this stele.Texts on such stelae often include a reference to transforming water poured over the stela into a curative libation, transferring the power of the stela’s spells and images to the worshipper, offering victory over dangerous animals and divine protection. Traditional Egyptian magic and religion such as this thrived throughout the fourth and third centuries BC despite the largely non-Egyptian origin of the country’s rulers at that time. See G. Pinch, Magic in Ancient Egypt, London, 1994.

For similar examples see British Museum acc. no. 1899,0708.23; also OC.350/EA36250: D. Antoine and M. Vandenbeusch, Egyptian mummies. Exploring Ancient Lives, Sydney, 2016, p. 107. Also the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, acc. no. 29.2.15. For further discussion see H. Sternberg-El Hotabi, 'Untersuchungen zur Überlieferungsgeschichte der Horusstelen', ÄA, 62, p. 55ff.

1

of

4